Payment processors pressure Steam and Itch to purge games, threatening major revenue loss if their demands aren’t met

Payment processing companies Visa and Mastercard control over 90% of all online transactions. When they threatened to withdraw their services from Steam, they knew that this move would cripple game sales and halt developer payouts, forcing the store to capitulate to Visa and Mastercard’s sudden demands.

Steam wasn’t the only targeted online game store – payment processors PayPal and Stripe gave Itch the same ultimatum: remove the games we disapprove of, or we’ll pull our services. As with Steam, this forced Itch to swiftly action a widespread deindexing of the games listed on their site.

☆ Delisting vs deindexing ☆

Delisting means removing the game entirely from the online store’s catalogue, i.e. the game is no longer available for purchase, and users who have already purchased the game may face difficulties accessing and playing it.

Deindexing means the game is no longer ‘searchable’, i.e. it won’t appear while browsing or searching on the site, but it does still exist in the catalogue, so those with a direct link, or who have already purchased a copy, will still be able to access the game.

It’s not only consumers’ freedoms that are under threat; developers also risk losing their income. As Itch stated in their July 24 update, they use payment processors to pay creators, meaning Steam and Itch would face difficulties paying developers for their game sales if the payment processing companies withdrew their services, as threatened.

While protecting revenue is understandable for these businesses, their decisions to appease megalithic corporations has caused ripples of resentment across the gaming industry. Uncertainty and betrayal are evident among developers who make the games these online stores use to turn a profit.

This is especially true for the sub-cultures and genres that were unfairly and disproportionately targeted – namely, visual novels. Steam removed 200+ visual novels from their storefront, many of those specifically being dating sims, putting the entire category at risk (Stop Censorship, 2025).

This article aims to explain current events, how the past decade has led to this recent development, and, ultimately, who to blame – that is, the legislation that began this slippery slope into censorship, back in 2018. I will also provide some options for action to take and a full list of references for further research.

♥ TLDR: To skip to the conclusion, click: here.

A concerning precedent

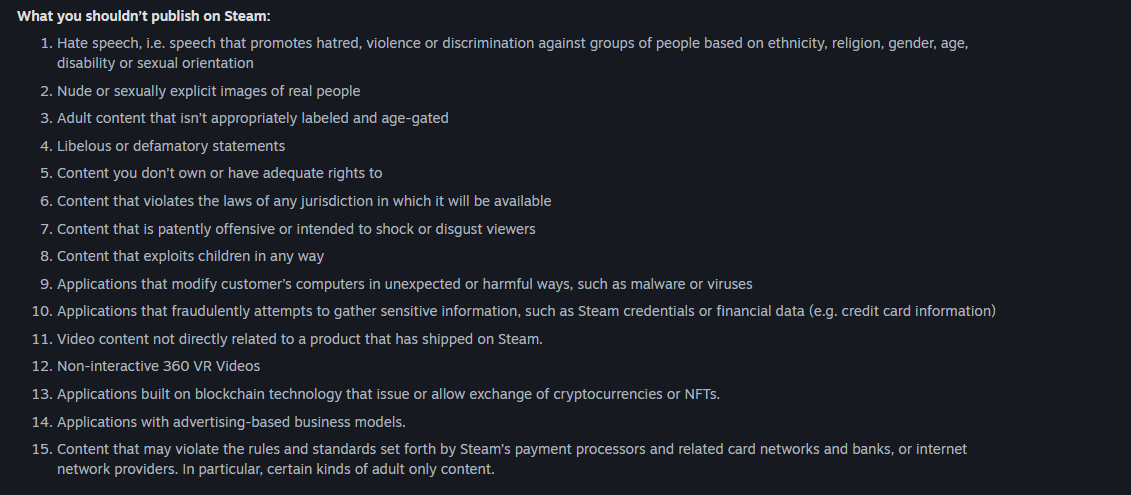

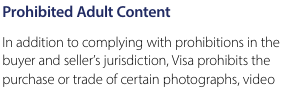

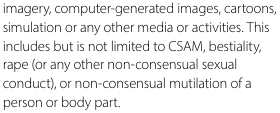

For now, the primary targets seem to be adult games; however, their guidelines are deliberately vague and could easily be interpreted to suit the companies’ political agenda. For example, Visa’s guidelines regarding prohibited content include ‘non-consenual mutilation of a person or body part’ (Visa, 2021), which means that gore and non-sexual violence could also be targeted, including major titles and franchises like GTA, CoD, Doom, Baldur’s Gate, or any of Hideo Kojima’s games, among many, many others.

The primary concern is the fact that corporations are able to do this at all. The recent hits on Steam and Itch have shown payment processors’ power to inflict censorship on a global scale. No company should be able to infringe on creative freedoms and cultural exports.

While the purge may begin with niche games, like dating sims and visual novels, allowing companies to choose what is harmful leads to suppression of other topics like LGBTQ+ resources, mental health, political dissent, or anything that conflicts with their interests and agendas (Stop Censorship, 2025).

How did we get here?

In this most recent digital censorship incident, the activist group known as “Collective Shout” have claimed responsibility for the payment processors’ decision to clamp down on online game stores.

On July 11, they published an open letter to the chief executives and presidents of several payment processors, namely: Visa, Mastercard, Paypal, Paysafe, Discover, and Japan Credit Bureau. Referring to the guidelines of these companies, they wrote, “We do not see how facilitating payment transactions and deriving financial benefit from these violent and unethical games, [sic] is consistent with your corporate values and mission statements.”

Note: the use of the words ‘violent‘ (again, not specifically target sexual violence) and ‘unethical‘ – a highly subjective term that can be interpreted vastly differently across cultural/sub-cultural groups.

Within 5 days, Steam had updated their onboarding documentation to clarify that games must adhere to the rules set by payment processors. 8 days later, Itch mass-deindexed all NSFW titles after Paypal and Stripe imposed their demands.

Although Collective Shout have claimed responsibility for the attacks on Steam and Itch, ultimately, the decision lies with Visa, Mastercard, PayPal, and Stripe.

Given the history of these companies cracking down on digital content they don’t approve of, it’s unlikely that Collective Shout, a fringe group on the other side of the world, had much of an influence on the payment processors’ actions besides providing a backlash scapegoat for a decision they already wanted to make.

A note on sexual violence in video games

There has been an outpouring of outrage to the wave of censorship, which Collective Shout claim is rooted in ‘misogyny and male violence against women’, despite many of the people protesting their campaign being women, and even victims of the violence themselves.

They claim that the stories found in these games extend beyond the realm of fiction, influencing the attitudes and behaviours of real perpetrators, which echoes the long-debunked myth that violence in video games leads to an increase in real-world violence.

Their position refuses to acknowledge the fact that games with stories of trauma help victims process their traumatic experiences. According to Dr. Heinz – a trauma and addiction research scientist at Stanford University – “Across all the different trauma-healing approaches and strategies, the unifying theme is that you do have to go back to the trauma in some way.”

This shows that games with themes reminiscent of traumatic experiences can provide a safe space for people to engage with their memories.

The distance of fiction acts a buffer, allowing access to traumatic memories without them becoming overwhelming. Not all games are created equally in this sense; however, particularly on Itch, there were games subsumed by this supposedly spooky category of “contains themes of sexual violence”, which do provide a safe space for survivors to process their experiences. These games should not be silenced. Any rule that oppresses people healing from trauma is an unacceptable rule, no matter how well-intended.

For example, the game Bi Lines, by indie game developer Bez, is specifically a game that “…depicts a man’s disbelief & pain over being sexually assaulted.” It was suspended after Itch deemed it in breach of their new restrictions, despite this being incorrect. Bez confirmed that the game “…depicts SA as a negative, awful thing, not something to be glorified.” This is just one example, but I chose it because Bi Lines embodies the idea of games with themes of sexual violence being a tool for healing – a tool which is now less available to the very people Collective Shout claim to campaign for.

Furthermore, creating and telling stories is an invaluable tool for healing after a traumatic incident. Suppressing the games made by survivors to process their own experiences is harmful, again, to the people Collective Shout claim to campaign for.

Personally, I have found romantic and NSFW games containing themes of sexual violence to provide space for processing and reframing my own traumatic memories. When I play a game or read a story, I am in control. I can stop at any time, and I get to choose how I interpret the scene. It allows me to access those memories and see them through a different lens. Even if I find it uncomfortable, to the point of distress, I can stop, calm down, and reflect on why I had that reaction, which deepens my understanding of myself and my emotions, and even remember my own memories more clearly.

I’m developing an indie visual novel myself that contains themes of sexual violence, that may not be allowed on Itch after their updated guidelines, despite the story being a creative and healing way for me to find meaning in something awful, and connect with others who share similar experiences.

Cutting Collective Shout some slack

In their statement, Collective Shout say, “We are real women in the world being inundated with threats of rape and violence and murder and just the worst kind of misogynistic abuse you can imagine.” Which, quite frankly, sucks. I have sympathy for people experiencing these kinds of threats and abuse – it is awful, and I hope that they find the support and care they need to recover and heal from these incidents.

Furthermore, I think that fighting against violence and discrimination is a worthy cause. It is true that Australian society still perpetuates and experiences harmful, gender-based discrimination. There is a very real threat to safety and health that deserves to be campaigned against.

My concern is that the passion they bring to this cause is being deflected to inefficient targets, and could be better spent elsewhere to maximise their impact on preventing violence and supporting survivors.

For example, campaigning for improved mental health care and education to assist victims and teach empathy, emotional awareness, stress tolerance, and communication skills; supporting shelters and refuges for victims of domestic violence; studying and teaching gender studies, womens’ history, or forensic psychology; working as or supporting social workers who provide practical, active support for victims on a daily basis.

This isn’t an exhaustive list, but the point I’m trying to make is that there are many hands-on, effective ways to fight against gender-based discrimination, without wasting that energy on video games that have already been proven to not be the problem. As the American Psychological Association (2015) put it:

“Violence is a complex social problem that likely stems from many factors that warrant attention from researchers, policy makers and the public. Attributing violence to violent video gaming is not scientifically sound and draws attention away from other factors.”

To summarise, I empathise with Collective Shout’s negative experiences with violence and aggression, and I support their goals of protecting victims of gender-based discrimination; I also believe their campaign against video games is a form of displacement, and their energy could be extremely valuable if directed towards a more appropriate target.

A history of censorship

I won’t go into detail on every censorship event – there are already great timelines out there that have already done exactly that. I will, however, highlight a few key events that I believe were a deliberate escalation to the Steam and Itch censorship we saw this year (July 2025, for future readers), and show exactly where these decisions stem from.

☆ Full timeline ☆

Stop Censorship have an excellent timeline that outlines significant digital censorship events. It’s concise and easy to follow, so I highly recommend checking it out if you want an effective overview of both payment processor pressure and legislation that has lead to the censorship, and even destruction, of various platforms since 2018 (7 years ago at time of writing).

Collective Shout may have claimed credit for the attacks on Steam and Itch, but the FOSTA-SESTA act was passed back in 2018, which set a precedent for censorship of digital media and platforms. This is an issue that predates Collective Shout’s recent efforts, and it is far bigger than their campaign.

2018: FOSTA-SESTA

The Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act (FOSTA) and Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act (SESTA) were two major pieces of legislation that were signed into law in 2018, which essentially created the first major exception to Section 230 (47 U.S.C), which was a law passed by U.S. Congress as part of the Communications Decency Act 1996.

To be brief, Section 230 was intended to protect online expression by preventing social media companies and other platforms from being held liable, or legally responsible, for unrelated, third-party content. I recommend Congress.gov for a more detailed overview and explanation of Section 230.

FOSTA-SESTA then created an exception to these protections, which set the wheels in motion for the digital censorship issues we see today. It is worth identifying that there were incidents prior to these Acts being passed; however, the scale at which the payment processors have enforced new restrictions has increased in recent years.

Prior to 2018

Jumping back slightly – I want to quickly note that, while Stop Censorship’s timeline begins in 2018, Twitter/X user MadamSavvy also compiled a timeline that goes back further, to 2016. Savvy highlights that, in 2016, Visa and Mastercard withdrew from Offbeat, which led to the platform shutting down. In 2017, they pulled out from FetLife, showing that their campaign against sex has been going for nearly a decade now.

2018-2019: The Great Tumblr Exodus

For us those of us who grew up on Tumblr, I’m sure we can all remember when the platform decided to ban all adult/NSFW content. Many users either left Tumblr entirely (myself included), or reduced their usage significantly. This banning was instigated by Apple’s App Store policies, showing a similar pattern of third-party companies bringing the ban hammer down on digital media they should not be allowed to censor. Other platforms like Patreon, Craigslist, Reddit, and Gumroad have all been hit with payment processor crackdowns in the past 9 years.

2024: Ramping up… to what end?

2024 was a huge year for payment processor censorship, with restrictions being forced upon more platforms than any previous year. The platforms targeted were largely Japanese media outlets, including Fantia, Fanza, and Toanoana. DLSite is a major international distributor and localiser of Japanese media, including manga, light novels, indie games, doujinshi, doujin games, and more. On March 26, 2024, DLSite made a statement:

“Credit card brands have made requests regarding services that include adult content, and DLSite has received similar requests.

We have given this request careful consideration, but as over half of all payments are made by credit card, and given the impact it will have on many users and groups, we have decided to comply with the request.

We deeply apologize for the fact that as we proceed with this issue, some words and phrases will no longer be able to be used in their original form.”

At the time, DLSite used Visa, Mastercard, and JCB to process credit card transactions. According to an article by Shohei Masubuch for NCB library (2024), this decision was likely influenced by a child pornography court case that Visa lost in 2022 after Brown Rudnick litigated against Pornhub, its parent company Mindgeek, and Visa, on behalf of approximately 100 victims (Brown Rudnick, 2022). Visa was named in this lawsuit as it was the company that Pornhub used to process credit card payments.

Visa argued that they were an innocent third-party, but the US federal court rejected their agument and Visa was found liable, on the grounds that, “Visa knew that MindGeek was monetizing child pornography, yet decided to continue to allow Mindgeek to be a merchant.” Visa denied these claims in a statement after the July 29 (2022) decision, stating that they are suspending their partnership with MindGeek, and that, “The allegations in this lawsuit are repugnant and stand in direct contradiction to Visa’s values and purpose.”

A similar argument was made by Collective Shout this year, in the campaign against Steam and Itch, that the content they named was in breach of the Visa’s values. It makes sense, given the context of the last decade, that Visa and Mastercard would see the situation as a potential legal issue that they want to nip in the bud before anyone tries to sue them again.

This shows that the FOSTA-SESTA act has allowed payment processors to be held liable for the merchants they do business with. While I would love to blame Visa, Mastercard, et al., for their actions – especially with the messy, crude way they have applied and enforced their restrictions – I can understand why, as corporations, they need to protect themselves from litigation. They do hold responsibility for their choices – particularly in the suddenness of their actions, preventing platforms from taking adequate measures to protect their own business interests – however, it is important to acknowledge where these decisions are stemming from.

So, who is to blame?

If we are to get to the heart of the issue and tackle the core cause of a long-standing digital censorship issue, it’s important to avoid getting swept up in solely the most recent event and its alleged instigators.

Yes, an Australian activist group petitioned payment processors to specifically target Steam and Itch. But, payment processors have been taking steps for nearly a decade now to stamp out any potentially litigious content from the merchants they partner with.

The reason that payment processors are able to be sued is due to US legislation – namely, FOSTA-SESTA. These Acts have allowed third parties to be liable for such content, which has directly led to these companies taking increasing measures to protect themselves from lawsuits.

The culprit at the top of the chain seems to be US legislation. American laws affecting American corporations are impacting international markets, resulting in the censorship of creative freedoms, particularly for 18+ works – even when they are legal and within the guidelines being forced on the platforms that distribute them.

What do we do now?

The most effective strategy for tackling digital censorship appears to be lobbying government bodies. Corporations need to be held in check, and the best way to do this is through legislation – which we can already see in how payment processors have reacted to current laws.

Primarly, campaigning against FOSTA-SESTA would allow for the removal of the exemption that allows payment processors to be sued for the content distributed by the platforms they provide their services to. Corporations survive by making profit, and therefore value revenue above all else. Whenever payment processors impose restrictions on their partners’ sales, they reduce their own capacity for income.

If they are free to partner with merchants who can then be responsible for their own content moderation, they have no reason to restrict the content of those merchants. They more sales the merchants make, the more revenue payment processors make from their partnership.

Payment processors are corporations, and they don’t want restrictions either. The more digital media they can process payments for, the more profit they make. If they can no longer be held liable, they have no reason for censorship, but they do have a pretty big motivation against it–their bottom line.

So, which legislation should be targeted?

Global legislation

While it’s clear that FOSTA-SESTA has had a large impact on recent and preceding events, the international market is exactly that – international. Other government bodies around the world have also enacted laws that affect the freedom to produce and purchase creative works.

The UK passed the Online Safety Act (2023), which led to many platforms choosing to block UK users rather than comply with the complex age-restriction requirements. This was intended to protect children and improve their online safety, but in reality, it prevented UK residents – both children and adults – from having access to major platforms, and therefore major online spaces that otherwise could have provided community, opportunities for UK cultural export, and income.

Those who do want to continue accessing those spaces are now forced to use VPNs and other roundabout measures. This decreases the online safety of UK users. Consider the prohibition, or legalising drugs and providing safe injecting rooms. History has shown that the best way to protect people is through legalisation and moderation. Conversely, criminalising something drives people to underground, dangerous alternatives.

It’s clear that protecting children is a common concern across many borders. All of the aforementioned legislation is designed to prevent children from online abuse and accessing adult content. None of that seems immoral to me. The issue is with the execution.

For example, throughout 2025, several US states have passed invasive age verification laws that have resulted in the same geoblocking the UK faced in response to the Online Safety Act. These age verification laws require users to provide government ID to access adult content, but how do users know that their ID can be safely stored and handled during this process? They can’t. The government can’t guarantee security of non-government platforms.

We all used to be kids and teens a long time ago. Buying alcohol under the legal drinking age is prohibited by law, but many people drink before they became a legal adult. It’s fairly common for people to have lied about their age on the internet, and getting a fake ID is frequent enough that it’s a staple trope in mainstream media.

My point is that, while age restrictions are important and do reduce the risks to minors, they’re not foolproof, and expecting platforms to flawlessly screen every single one of their users isn’t realistic or reasonable. The kids will find a way, no matter the restrictions.

Take action

In the initial reaction to the Steam and Itch purge, a change.org petition was formed. While they aren’t legally binding, petitions do put a number to the outrage. Corporations and governments love statistics, so having a figure to present adds weight to any argument, lobby, or campaign. The petition is still ongoing, so it’s not too late to add your signature!

I’ve referenced them before in this article, but I’m doing it again – Stop Censorship has a page dedicated to detailing actions that can be taken to combat digital censorship. These options are organised into three categories, based on ‘engagement level’ – so, if you’re completely new to this, there is a beginner option that takes you through some of the fundamentals, with less complex actions that are more accessible.

They also provide scores for impact and accessibility, allowing for more thoughtful decisions around which actions are going to be the best balance between effect and sustainability. If you want to do something to fight against digital censorship, I highly recommend checking out Stop Censorship for their wealth of information on the topic.

Contacting payment processors

The other strategy that has been circulating, is calling payment processors to lodge complaints. 10k Phone Calls has phone numbers and email addresses to assist with contacting the revelant businesses, as well as templates for emails and scripts for phone calls.

I know the prospect of making a phone call can be spooky for millennials, and inconceivable for younger generations, but this advice (provided by a member of the Sweet & Spicy discord server) may help to provide an expectation of how the interaction might play out:

“Call VISA/MasterCard/STRIPE/Paypal, you’ll be on hold for a while because everyone is calling, and say you’d like to lodge a complaint. Then when they ask what this is in regards to, just start reading your script. Sometimes the rep will cut you off once they find out what the complaint is about, but just ask whether or not the phone call complaints are reported, if they say yes, then say you want your call to be reported and heard and then read your script. If they say no, that’s really weird and just keep insisting and eventually they will try to transfer you to a supervisor or something. The longer the message the better since that’s the point. … We don’t need to be aggressive – just persistent.”

Contacting governments

My advice is to tailor the campaigning to the local context. For example, in the US, it might be better to talk about unelected corporations infringing on the freedoms of Americans to make a living off of their creative works. In Japan, it is more relevant to discuss the fact that Japanese cultural exports are being censored by American corporations. In Australia, it would likely be effective to warn politicians of how the actions of an extremist group are tarnishing the reputation of Australia in the international gaming industry, particularly as the Australian gaming industry is only just beginning to establish itself in international markets.

It’s helpful to think about how the actions of these companies specifically impacts the politicians you are reaching out to, and what they are likely to care about – typically reputation and revenue – as well as which political points they can use to garner more votes.

That being said, all of that requires a lot of thought, time, and energy, which can be draining, particularly if a sustained campaign is needed. In this case, a template letter or email that can be easily copied and pasted en masse is significantly more effective than only contacting someone once because it was too exhausting to repeat.

Go elsewhere

While Steam and Itch in particular have been forced into a corner, the fact that they capitlutated to the demands is still disappointing. Sourcing alternative platforms is another way to push these online storefronts into doing something about these restrictions rather than meekly enforcing them.

On July 24, JAST BLUE tweeted about the situation at Itch, asking developers who had been affected by the bans to contact them for assistance with getting set up to sell their BL and/or Otome titles through their storefront. The following day, JAST followed up by adding that any SFW/NSFW visual novels ‘affected by the recent waves of censorship’ were welcome to get in touch to see if their game is a good fit – and if so, assist them with selling their game through the JAST Store.

Don’t give up hope

What do we do next? We hold onto hope. This infringement on an industry we love can easily lead to a downwards spiral of doom and gloom. These companies have taken a step in a horrible direction, but this is exactly the kind of warning move that gives us a chance to protest and show them that we won’t accept this.

There are things we can do to prevent the doom and gloom scenario. Every time that draining, heavy, melancholy feeling creeps in, telling you it’s hopeless because nothing any of us do will matter, remind it that people are already doing things that matter, and there are things we can do together to keep the pressure going.

So please, take breaks, take care of yourself, and remind yourself that every signature on that petition counts, every single action counts, towards a much bigger movement. Marathons are finished through stamina, pacing, and continually putting one foot in front of the other.

You’ve got this, we’ve got this, and it’s worth fighting for.

Contributors

I wanted to thank the members of the Sweet & Spicy discord server for assisting with this research. I asked for references and links that they found informative and helpful, and boy did they deliver. Their contributions proved invaluable in writing this article; so, to the people on the server who answered my research casting call: thank you – your assistance is very much appreciated ♥

References

Below is a list of sources I used to write this article. I’ve separated them into “primary” and “secondary” sources because I studied ancient history at university and that made sense to my brain. Essentially, the intent is to list direct references to the companies and parties mentioned in the article, e.g. statements by Visa, as “primary sources”, and other articles and research I read by third-parties as “secondary sources”.

Side note: I originally formatted them in APA in a google doc, but when I tried to paste them into wordpress, all hell broke loose. Below is my best attempt at formatting nicely in wordpress, but I apologise in advance to all the academics in the room, and to myself for the pain I put me through.

Please feel free to use these references as a starting point for your own research into digital censorship – I hope they will be helpful!

Primary sources

- 10k Phone Calls. (Date Unknown). 1,000 phone calls destroyed free expression. 10,000 phone calls can take it back.

- American Psychological Association. (2015, February). APA Resolution on Violent Video Games.

- Bez. (2025, July 25). Of all the games [Itch] chose as a reason to suspend me… [Posted on Bluesky].

- Brown Rudnick. (2022, August 05). Visa Suspends Ad Payments on MindGeek After Landmark Ruling Obtained by Firm.

- Brown Rudnick. (2022, August 01). Brown Rudnick Secures Landmark Ruling Against Visa in MindGeek Child Porn and Sex Trafficking Case.

- Collective Shout. (2025, July 11). Open letter to payment processors profiting from rape, incest + child abuse games on Steam.

- Collective Shout. (2025, July 18). Since we launched our campaign calling on Payment Processors… [Posted on X / Twitter].

- Congress.gov. (2024, April 1). Section 230: An Overview.

- Gov.UK. (2025, April 24). Online Safety Act: explainer.

- Itch.io. (2025, July 24). Update on NSFW content.

- Itch.io. (2025, July 31). Reindexing adult NSFW content.

- https://itch.io/t/5149036/reindexing-adult-nsfw-content

- Note: this action to reindex adult NSFW content primarily applies to free content – with paid content slowly being re-indexed, but even then, still within the guidelines recently updated as a result of payment processor pressure.

- JAST. (2025, July 25). Not just BL or Otome, either. [Posted on X / Twitter].

- JAST BLUE. (2025, July 24). If you have a BL or Otome title that’s been affected by today’s Itch actions… [Posted on X / Twitter].

- Kelly, A. F. (2022, August 04). We do not tolerate the use of our network for illegal activity. Visa.

- Verdeschi, J. (2021, April 14). Protecting our network, protecting you: Preventing illegal adult content on our network. Mastercard.

- Ryoko, Zero. (2025, July). Tell MasterCard, Visa & Activist Groups: Stop Controlling What We Can Watch, Read, or Play. Change.org.

- Steamworks. (2025, July 16). Onboarding.

- Stop Censorship. (Date Unknown). Join the Fight for Digital Freedom.

- U.S. Department of Justice: Office of Public Affairs. (2024, September 24). Justice Department Sues Visa for Monopolizing Debit Markets.

- Visa. (2021, April). Payment Facilitator and Marketplace Risk Guide.

- https://usa.visa.com/content/dam/VCOM/regional/na/us/partner-with-us/documents/visa-payment-facilitator-and-marketplace-risk-guide.pdf

- Note: the guidelines regarding prohibited adult content are on page 14

Secondary sources

- Center for Trama and Embodiment. (2025, February 5). Storytelling and Complex Trauma Healing: The Power of Narrative in Recovery.

- Ferguson, C. (2016). New Evidence Suggests Media Violence Effects May Be Minimal. Psychiatric Times.

- Krouse, L. (2022). Here’s What ‘Processing’ Trauma Really Means–And How It Helps You Heal. SELF.

- Litchfield, T. (2025, July 21). Australian anti-porn group claims responsibility for Steam’s new censorship rules in victory against ‘porn sick brain rotted pedo gamer fetishists’, and things only get weirder from there. PC Gamer.

- MadamSavvy. (2025, July 25). This is my attempt to map Visa and Mastercard Censorship… [Posted on X / Twitter].

- Montanaro, M. (2025, July 21). Visa and Mastercard Are Reportedly Censoring Video Games Alongside Australian Activist Group Collective Shout. That Park Place.

- Shohei Masubuch (2024, March 26). [Discussion] Why did DLSite come under pressure from Credit card brands to regulate expression? NCB Library.

- Psychology Today (Date Unknown). Displacement.

- Ratcliff, J. (2025, July 16). Steam Begins Removing Games After Updating Its Publishing Rules. Game Rant.

- Shell, D. (2025, August 3). Australian campaign group sparks NSFW game takedowns and a debate about free speech. ABC news.

- SteamDB. (2025, July 16). Steam has added a new rule disallowing games that violate the rules and standards set forth by payment processors… [Posted on Bluesky].

- Stop Censorship. (2025, August). Steam & Itch.io Under Escalating Pressure.

- Stop Censorship. (Date Unknown). Censorship Timeline.

- Stop Censorship (Date Unknown). Join the Fight for Digital Freedom.

Thank You

~☆ Patrons ☆~

Kristin_Eve

Jada Brown

Meghan Hadley

Vilicus

Valeria Ten

About the Author

oli tempest

A yandere and toxic romance enthusiast with a passion for problematic ikemen, melodrama, and all things fae. Pronouns are They/Them.

Writer, game dev, and founder of Sweet & Spicy Reviews and Grimamour Games.

Fun fact: Colour blind, but only for red flags.

Contact Us

For all enquiries, please email us at sweetnspicyreviews@gmail.com or via the social media links below:

This was a great article summarizing the whole situation! I adore the bibliography at the end. Very helpful! I’ve taken a two week break from activism, but this has gotten me re-charged and re-oriented. Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yay, thank you! It’s definitely a good idea to take breaks – I’m doing the same at the moment. I’m glad to hear you’re feeling re-charged and re-oriented though, and I’m happy I could help ^_^

LikeLiked by 1 person